The Hunter and the Bear

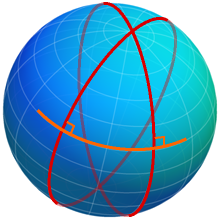

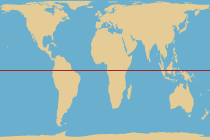

A hunter is tracking a bear. Starting at his camp, he walks one mile due south. Then the bear changes direction and the hunter follows it due east. After one mile, the hunter loses the bear’s track. He turns north and walks for another mile, at which point he arrives back at his camp. What was the colour of the bear?

There are multiple places on Earth where this could happen, but only one where you can find bears…

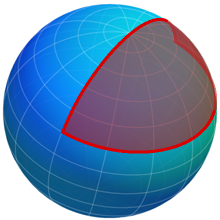

An odd question – not only is the colour of the bear unrelated to the rest of the question, but how can the hunter walk south, east and north, and then arrive back at his camp? This certainly doesn’t work everywhere on Earth, but it does if you start at the North pole. And therefore the colour of the bear has to be white.

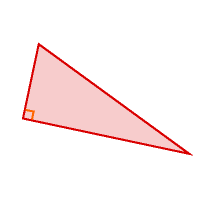

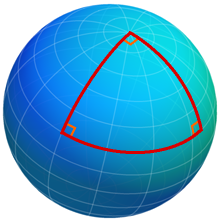

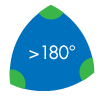

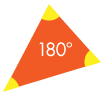

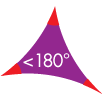

A surprising observation is that the triangle seems to have two right angles – in the two bottom corners. Therefore the sum of all three angles is greater than 180°, something that we proved to be impossible.

All these things are based on the fact that geometry works differently in flat space than it does on curved surfaces like a sphere. There are many other kinds of geometry, different kinds of space, with different properties. In this article we will explore a few of them.

Metric Spaces

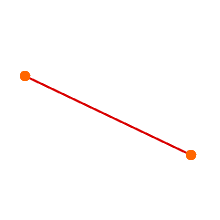

One of the most fundamental concepts in geometry is that of distance. Intuitively, the distance between two points is the length of the straight line which connects them. There are no straight lines on the surface of a sphere, but even on a flat surface we can find a number of different ways to define the meaning of distance:

|

|

|

|

EUCLIDEAN METRIC The most intuitive way to measure distance is the straight line between two points. |

MANHATTAN METRIC On the other hand, in some cities, the distance between two points is only measured along horizontal or vertical lines, not directly. |

BRITISH RAIL METRIC In the UK, the distance, via rail, between two distinct points always has to go via London. |

We can define the distance between two points in space, like above, but we can also define the distance between other objects. For example, the distance between two images could tell you about their similarity: if the images are similar their distance is small, and if they look very different their distance is large. The distance between two human beings could tell you about how closely they are related.

We need some more information to accurately describe these two new “distance functions”, but there are three properties which all distance functions must have in common:

- The distance between a point and itself is zero, and the distance between two distinct points is never zero.

-

The distance between points A and B is the same as the distance between points B and A.

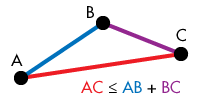

- The direct distance between points A and C is always at least as small as the distance between points A and B plus the distance between points B and C. This is called the Triangle Inequality.

The various “distance functions” are called Metrics, and the corresponding “spaces” are called Metric Spaces. There are many other distance functions, similar to the ones above.

Spherical Geometry

In the introduction we discovered that we can draw a triangle on the surface of a sphere in which the angles add up to more than 180°. The amount by which the sum of the angles in a spherical triangle exceeds 180° depends on the size of a triangle compared to the size of the entire sphere. Large triangles have a greater sum of angles than small triangles.

This is only one of the facts which distinguish geometry on flat surfaces (Euclidean geometry) from spherical geometry.

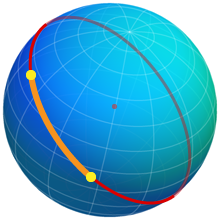

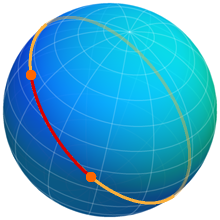

Even drawing a “straight” line between two points on the surface of a sphere is problematic. There are many different possibilities, but the shortest line lies on an imaginary “equator” through the two points. These equators are called great circles and the great circle segments, called geodesics, are what we mean when we refer to “lines” in the following section.

| EUCLIDEAN GEOMETRY | SPHERICAL GEOMETRY | |

|

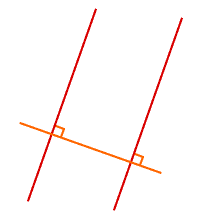

PARALLEL LINES Unlike on a flat surface, you can’t have parallel lines on a sphere. Any two lines (great circles) will intersect. |

|

|

LINES BETWEEN TWO POINTS On a flat surface, there is a unique straight line between two points. On a sphere, there are at least two lines/geodesics between distinct points, and infinitely many lines between opposite points on the sphere. |

|

|

2-GONS On a flat surface, you can’t have polygons with only two sides (2-gons), but you can on a sphere. |

|

|

RIGHT ANGLES Triangles in a flat surface can have at most one right angle. Triangles on a sphere can have two or even three right angles. |

|

Spherical geometry is much harder to visualise than flat Euclidean geometry, but we do live on a sphere rather than a disk. Since Earth is so large compared to us, the effects of spherical geometry are hardly noticeable in everyday life and the surface looks almost flat at any one point. But understanding spherical geometry is important for navigation and cartography, as well as astronomy and calculating satellite orbits.

Projections

The most common problem with living on a sphere arises when designing maps – it is impossible to accurately represent the 3-dimensional surface of Earth on 2-dimensional paper.

By “stretching” the surface in various ways, it is possible to create projections of Earth’s surface onto a plane. However some of the geographical properties, such as area, shape, distance or direction, will get distorted.

|

|

|

| The Mercator Projection | The Gall-Peters Projection | The Mollweide Projection |

The Mercator projection significantly distorts the relative size of various countries, while the Gall-Peters and Mollweide projections distort straight lines and bearings. There are many other projections to represent Earth on maps, and you often use different projections to show certain parts of Earth, or for particular applications such as nautical navigation.

The underlying reason for having to distort Earth’s surface in order to represent it on a 2-dimensional map is the fact that it has a positive curvature. Only shapes with a zero curvature, such as cubes, cylinders or cones, can be represented in a lower dimension without distortion.

The curvature of a curve at a particular point is the inverse of the radius of the circle which best approximated the curve at that point. For a straight line, this would be a circle with infinite radius, so the curvature is 1/∞ = 0. For points on a 2-dimensional surface, you can find many different curvatures along different directions. The principle curvature is the product of the smallest and the largest of these curvatures. Points with a positive curvature are called elliptic points. Points with a negative or zero curvature are called hyperbolic or parabolic points respectively.

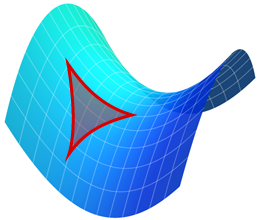

Hyperbolic Geometry

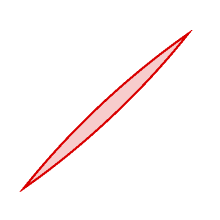

The surface of a sphere is curved “inwards” (a positive curvature). Instead we could think about what happens if space is curved “outwards” at every point (a negative curvature), forming a surface which looks like a saddle. This gives rise to Hyperbolic Geometry.

|

|

|

| Spherical triangle | Euclidean triangle | Hyperbolic triangle |

Hyperbolic surfaces appear in nature and technology, usually because of their large surface area or because of their physical strength:

|

|

|

| Hyperbolic cooling towers at power plants | Hyperbolic corals | Hyperbolic flower vase |

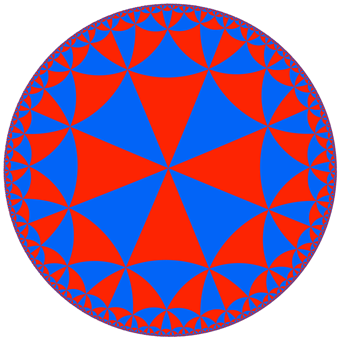

Unlike the surface of a sphere, hyperbolic space is infinite. However we can create a finite projection of hyperbolic space onto a flat surface:

|

|

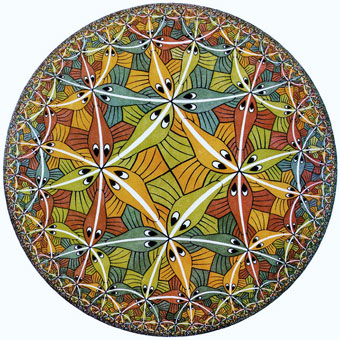

| A hyperbolic tiling consisting of triangles | Circle Limit III by M. C. Escher (1898 – 1972) |

These projections are called Poincaré disks, named after the French mathematician Henri Poincaré (1854 – 1912). In hyperbolic space all the triangles (left) would have “straight” edges as well as the same size and shape. In the projection, space is distorted in a way that makes triangles towards the centre look bigger and triangles towards the edge look much smaller. There are infinitely many of these triangles, forming an infinite regular tessellation in hyperbolic space.

Click anywhere inside the disk to add a point. Create a second point to form a hyperbolic line. Once placed, you can change the lines by dragging the endpoints. While the lines may appear curved in the Poincaré disk projection, they are straight in hyperbolic space. Can you make hyperbolic triangles, squares or other shapes?

Special Relativity asserts that, depending on how fast you are moving, time runs faster or slower and distances appear longer or shorter. These effects are only noticeable if you move very, very fast – but they are important to consider for example when designing satellite navigation systems.

One way to model the distortions of space and time predicted by special relativity is to think about space and time as being hyperbolic rather than “flat” and Euclidean. Hyperbolic geometry can be used to add velocities and calculate the effect of accelerations.

Topology

When defining Metric spaces at the beginning of this chapter, the key concept was that of distance. In contrast, in Topology we don’t care about the distance between two points, only whether it is possible to move from one point to the other. Two objects are topologically equivalent, or homeomorphic if we can transform one into the other by continuously bending and stretching it, without having to cut holes or glue boundaries together.

Many letters in the alphabet are topologically equivalent. Imagine they are made of rubber and can be easily stretched, but not cut or glued together.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Similarly, a teacup and a doughnut are topologically equivalent and can be transformed into each other – the subject of many jokes about topologists. The mathematical name for doughnut shapes is torus.

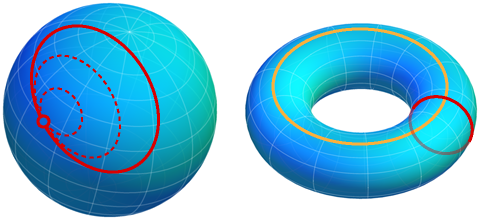

On the other hand, a torus and a sphere are not equivalent because one has a hole and the other one doesn’t. They have different topological properties: for example, any “rubber loop” embedded on the surface of a sphere can be compressed to almost a point. On the surface of a torus, there are some rubber loops which can’t be compressed in that way:

Henri Poincaré (1854 – 1912)

In three dimensions, it is intuitively clear that any shape on which you can condense all rubber bands to a point has to be homeomorphic to a sphere. Henri Poincaré conjectured that the same is true for spheres in 4-dimensional space: the Poincaré Conjecture. For more than 100 years, this was one of the most important unsolved problems in mathematics, including one of the seven Millennium Prize Problems with a prize money of $1,000,000.

In 2002, the conjecture was proven by the Russian mathematician Grigori Perelman (*1966) using a concept called the Ricci Flow. It is the only Millennium problem that has been solved to date – but Perelman declined both the prize money and the Fields Medal, the most prestigious award in mathematics.