Triangles and TrigonometryPythagoras’ Theorem

We have now reached an important point in geometry – being able to state and understand one of the most famous

Pythagoras’ Theorem

In any right-angled triangle, the square of the length of the hypotenuse (the side that lies opposite the right angle) is equal to the sum of the squares of the other two sides. In other words,

The converse is also true: if the three sides in a triangle satisfy

Right angles are everywhere, and that’s why Pythagoras’ Theorem is so useful.

Here you can see a 6m long ladder leaning on a wall. The bottom of the ladder is 1m away from the wall. How far does it reach up the wall?

Notice that there is a right-angled triangle formed by the ladder, the wall and the ground. Using Pythagoras’ theorem, we get

Whenever you’ve got a right-angled triangle and know two of its sides, Pythagoras can help you find the third one.

Proving Pythagoras’ Theorem

Pythagoras’ theorem was known to ancient Babylonians, Mesopotamians, Indians and Chinese – but Pythagoras may have been the first to find a formal, mathematical proof.

There are actually many different ways to prove Pythagoras’ theorem. Here you can see three different examples that each use a different strategy:

Rearrangement

Have a look at the figure on the right. The square has side length

Now let’s rearrange the triangles in the square. The result still contains the four right-angles triangles, as well as two squares of size

Comparing the area of the red area and the rearrangement, we see that

This is the original proof that

Algebra

Here we have the same figure as before, but this time we’ll use algebra rather than rearrangement to prove Pythagoras’ theorem.

The large square has side length

It consists of four triangles, each with an area of

If we combine all of that information, we have

And, once again, we get Pythagoras’ theorem.

Similar Triangles

Here you can see another right-angled triangle. If we draw one of the altitudes, it splits the triangle into two smaller triangle. It also divides the hypotenuse c into two smaller parts which we’ll call x and y.

Let’s separate out the two smaller triangles, so that it’s clearer to see how they are related…

Both smaller triangles share one angle with the original triangle. They also all have one right angle. By the AA condition, all three triangles must be

Now we can use the equations we already know about similar polygons:

But remember that

Once more, we’ve proven Pythagoras’ theorem!

Much about Pythagoras’ life is unknown, and no original copies of his work have survived. He founded a religious cult, the Pythagoreans, that practiced a kind of “number worship”. They believed that all numbers have their own character, and followed a variety of other bizarre customs.

The Pythagoreans are credited with many mathematical discoveries, including finding the first

“Pythagoreans celebrate sunrise” by Fyodor Bronnikov

Calculating Distances

One of the most important application of Pythagoras’ Theorem is for calculating distances.

On the right you can see two points in a coordinate system. We could measure their distance using a ruler, but that is not particularly accurate. Instead, let’s try using Pythagoras.

We can easily count the horizontal distance along the x-axis, and the vertical distance along the y-axis. If we draw those two lines, we get a right-angled triangle.

Using Pythagoras,

This method works for any two points:

The Distance Formula

If you are given two points with coordinates (

Pythagorean Triples

As you moved the

One famous example is the 3-4-5 triangle. Since

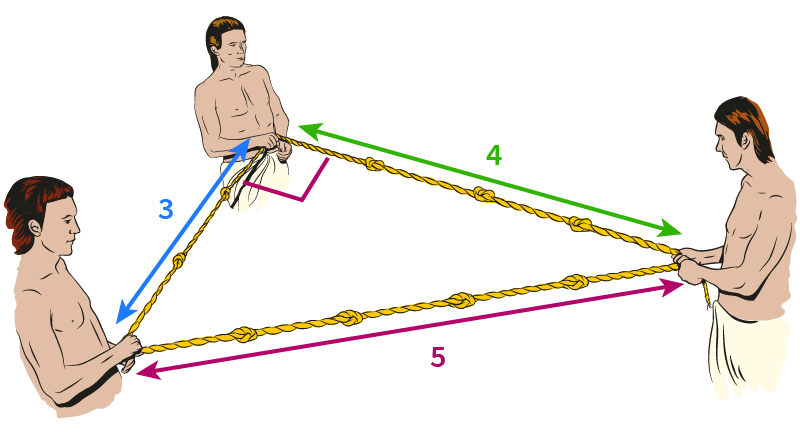

The ancient Egyptians didn’t know about Pythagoras’ theorem, but they did know about the 3-4-5 triangle. When building the pyramids, they used knotted ropes of lengths 3, 4 and 5 to measure perfect right angles.

Three integers like this are called

We can think of these triples as grid points in a coordinate systems. For a valid Pythagorean triples, the distance from the origin to the grid point has to be a whole number. Using the coordinate system below, can you find any other Pythagorean triples?

Do you notice any pattern in the distribution of these points?